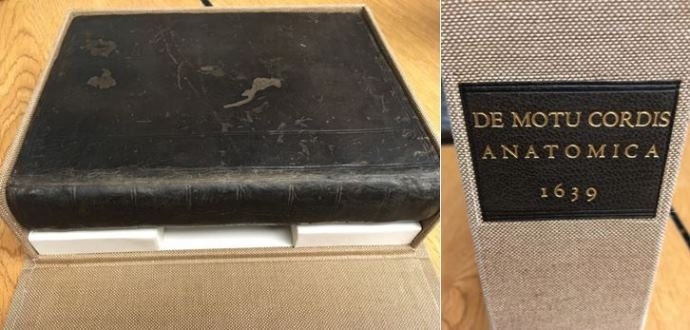

Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus by William Harvey is known as the first book to correctly describe the human circulatory system. Not having a medical background, this tidbit of medical history trivia was foreign to me until several months ago when I discovered an edition of this book from 1639 in our history of medicine collection.

Currently our entire history of medicine collection is in storage as we complete what will be a spectacular library renovation; so I’ve only been able to see assorted pieces of the collection here and there. Each piece has been more fascinating than the last. An orthopedic surgeon’s kit, an old book of anatomical drawings -- just the kind of things a history geek like myself laps up with enthusiasm. But when I was able to pick up a book from 1639 with such incredible history, I was absolutely ecstatic.

What is it about not just learning history, but actually being able to touch it? You can’t help but think of the hands that touched the object and are now long gone from this world. What did their world look like? What did the room they were reading it in look like? What did their clothes look like? Imagine how different their understanding of medicine and the human body was.

I always say that my job as a librarian is to “make information discoverable.” One of the ways that we do that as medical librarians is by preserving the past in our archives, but preserving these objects of history means so much more than just preserving the information about them. I can tell you all about de Motu Cordis and its importance to modern medicine. I can tell you about Harvey’s use of the scientific method and his challenges to the traditional method. But to actually see the book from 1639, to think about the man reading it, think about his world… that gives you something greater than information. That gives you a connection to the past and those who came before us to create the world we look around and see today. To be a librarian and play a part, albeit a small part, in the preservation of something so special is truly amazing.

So I ask my audience, what are some of the pieces in your collections that get you truly excited?

-Marie C. Cirelli

Harrell Health Sciences Library: Research and Learning Commons

Penn State College of Medicine

About de Motu Cordis:

Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus (Concerning the motion of the heart and blood) was first published by William Harvey in 1628. Harvey first presented his ideas on the circulation of blood in 1616 to the College of Physicians, but his ideas evolved into his final published piece over several years in Lumleian Lectures to the College of Physicians (Silverman, 2007). Because of Harvey’s observations he is known as “the founder of modern physiology.” Although he is credited with being the first to correctly describe the circulation of blood, Ibn an-Nafis, a physician in Cairo in the thirteenth century may have actually been the first. However, an-Nasifs’ work never circulated (pun intended) outside of the eastern Mediterranean and little headway was made in significant anatomical discoveries until the mid-Sixteenth Century (MacLean, 2007). What is considered the birth of modern medicine began with Andreas Vesalius’ work De Humani Corporis Fabrica in 1543 where he described the anatomy of a human body based on human, not animal dissection (Silverman, 2007). This was previously not done because of religious and ethical reasons (MacLean, 2007). In the wake of medical discoveries Harvey’s work also challenged traditional thinking. Harvey used what is now known as the scientific method by experimenting on and observing the hearts of various animals (Ribatti, 2009). His findings challenged the view of the heart previously based on the Aristotelian interpretation of it as a center of personality and behavior. The heart now became merely a mechanism to pump blood through the body (MacLean, 2007).

MacLean, R. (2007). June 2007: De motu cordis. GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DEPARTMENT: Book of the Month. Retrieved from http://special.lib.gla.ac.uk/exhibns/month/june2007.html

Ribatti, D. (2009). William Harvey and the discovery of the circulation of the blood. J Angiogenes Res, 1, 3. doi:10.1186/2040-2384-1-3

Silverman, M. E. (2007). De Motu Cordis: the Lumleian Lecture of 1616: An imagined playlet concerning the discovery of the circulation of the blood by William Harvey. J R Soc Med, 100(4), 199-204.